₹ 71,962. This is the amount Short Straddle Strategy could make in three months if one is willing to engage a capital of ₹ 7,00,000. Seventy thousand rupees in three months on seven lakhs makes a monthly return of 3.4% and an annual return of 40%. I know, you would say 40% return that sounds crazy to that I would add: It’s not crazy its ridiculous. Let me try to breakdown the whole process.

What are we doing?

In short we are selling options.

A option is a contract between two parties Seller and Buyer. Seller sells the option contract to Buyer for a few bucks. In return buyer gets an option to buy a share of a company at an agreed upon price on a predetermined date.

Say Sameer the seller sells Bobby the buyer an option contract that Bobby can buy share of Reliance Industries Limited from Sameer for ₹ 2,600 on 28th Oct. On 28th Oct, it will be Bobby’s choice to buy the share or not. If Reliance would be trading at more than ₹ 2,600, Bobby will be interested in buying it from Sameer @ ₹ 2,600. While if its less than ₹ 2,600 Bobby can ignore the contract. Sameer on other hand will be obliged to sell the shares if Bobby chooses to buy. If Sameer doesn’t have Reliance’s share with him, he will have to buy it from market and sell it to Bobby @ ₹ 2,600. And yes even if he bought it at a higher price and thus making a loss in the whole deal. Seems like Bobby has a big advantage in this options contract and this is because options are designed to favour the buyer. In that case what in the contract for the seller? Well while initiating the contract Seller will ask for an upfront payment. So in our case Bobby will have to pay an amount say ₹ 50 to Sameer upfront and when the day comes may or may not exercise the option.

We in our Short Straddle Strategy take Sameer’s position and sell options contract on Nifty. Why selling options and not buying and Why Nifty? Let’s cover that in next segment.

Why we sell contracts?

We know options contract are designed to favour the buyer but in reality the compensation seller gets makes the contract a fair deal for both. Consider current prices, Reliance last traded at ₹ 2520 and an option to buy Reliance at this price on 28th Oct was sold at ₹ 84. So let alone the decline in Reliance’s share price, even if the price remains same for the whole month, seller stands a change to make ₹ 84. This is a pretty good deal for the seller. If the share price goes down, seller makes money. If the share price stays same, seller makes money. If the share price goes up a bit (but not much), seller still makes money. Buyer only makes money when share price goes up drastically.

Although it happens seldom that buyer makes money on an option contract, but when that happens they make huge money with a potential to destroy seller in one go. So how can a seller safeguard themselves from such huge blows? This is why we trade in NIFTY, let’s cover that in next segment.

Why we sell NIFTY contracts

NIFTY contracts are the most liquid options contract on the exchange. This means at any given time maximum number of traders are willing to buy/sell NIFTY contracts than any other contract. Open interest is a good metric to judge liquidity, higher the open interest higher the liquidity. Open interest for NIFTY options is around 15000 while highest open interest for Reliance’s options is just 4000.

Seller can limit their losses by offloading current contracts to another seller by take a small loss. In our earlier earlier example Sameer sold an option to Bobby for ₹ 50 to buy Reliance share at ₹ 2,600 on 28th Oct. If Sameer feels Reliance price will shoot up drastically and he would end up making a big loss, he can offload the contract to another seller by booking a small loss in his books. This offloading will be possible only if there are sellers available to be offloaded. NIFTY having liquidity ensures this.

How we implement the strategy

The NIFTY index moves throughout the day, it has its high points and low points before the trading day closes. In the short straddle strategy we try to enter a position where NIFTY is within our grasp. If the the index moves out of grasp, we alter our position to re grasp it. We continue to play the game of taming the bull until the index settles. During this game the longer we hold our grasp more money we make and we loose money altering our positions.

In order to limit the losses we also keep a track of profit or loss we are at for the day. If the loss incurred is more than our limit, we quickly offload our positions to another seller by booking the loss and exit the market.

We take following steps int he strategy:

- Check the Latest Price of NIFTY

- Decide if the current position is good or we need to alter it

- If altering the position, decide the new position

- Track profit or loss we have booked

- If the losses are beyond our limit exit the market

We keep on repeating these steps and take decisions accordingly. In the end it becomes the game of taking quicker actions, if the index price went too far quickly adjust the positions, if the loss are too high quickly exit the market. In fact faster we are able to repeat these steps more efficient we become and more profit we book. It’s not humanly possible to run these steps fast enough and thus we designate a dedicated computer for it. Due to faster processing we are able to repeat these steps every second.

By analysing the market every second we ensure the index doesn’t move too far for us to not be able to handle the shift. Or by tracking losses every second we ensure the moment we hit our loss limit we are out of the market the very next second thus not experiencing soared losses.

Back to the Interesting Stuff

We backtested the Short Straddle Strategy on NIFTY for three months 17th May 2021 to 13th August 2021.

The capital required for the strategy is ₹ 7,00,000. We need to have this amount in our account to be able to run the strategy.

We set our max loss per day limit to ₹2,000. This means moment we hit loss of ₹ 2,000 we exit the market. The actual loss might come to around ₹ 2,500 for some days.

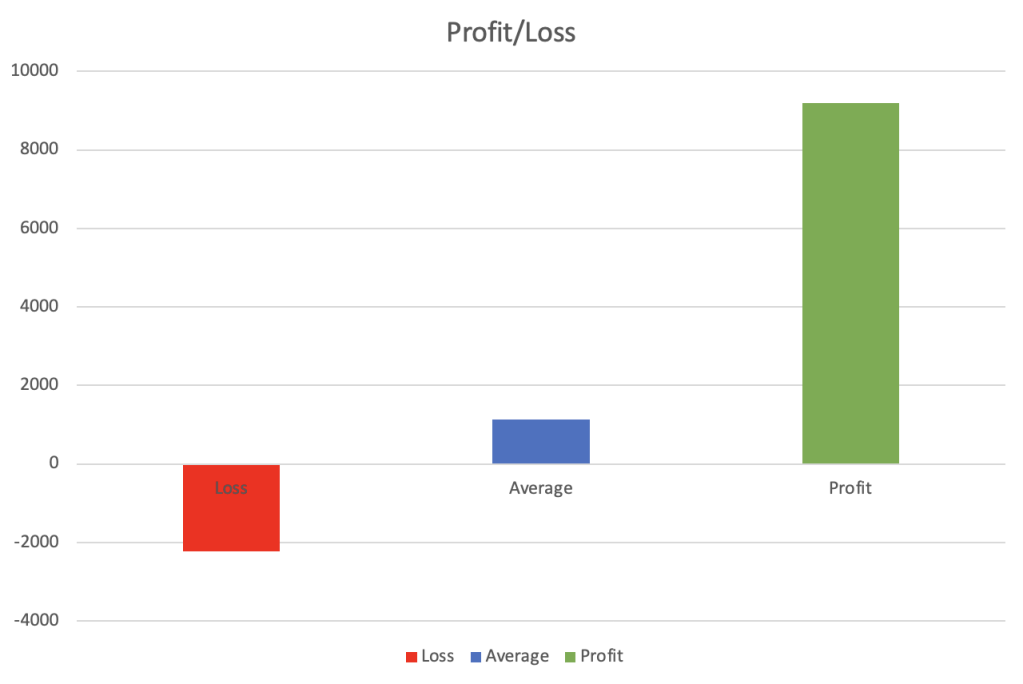

On Tuesday, June 1st 2021 we incurred a loss of ₹ 2,235. This was our max loss during the entire period.

On Thursday, June 24th 2021 we made a profit of ₹ 9200. This was the max profit we made during the period.

On average we made a profit or ₹ 1,124 daily.

Out of total 64 trading days, we made profit on 43 days while loss on 21 days. On the days we made profit we made average of ₹ 2,508 while on loosing days we lost ₹ 1,710.

There were days when the index movements were at peak.

- On Monday, June 21st 2021 NIFTY moved up 220 points, we made a profit of ₹ 3,982 that day.

- Two days later Wednesday, June 23rd NIFTY fell 175 points. We lost ₹ 2,000 that day.

- On Tuesday, August 3rd we were on track to make a big loss of ₹ 4,282. But to due our max loss mechanism our losses were limited to ₹ 2,047

We usually make money when we hold our position for long. Thus on an average we make a loss to get a hold on position. Once the index movements slows down we start to book profits. Again mid day our profits become stagnant but towards the end of the day we make big leaps.

This has been a brief analysis of the Short Straddle Strategy when run of NIFTY index. The Short Straddle is amongst the most basic options selling strategy and is wide known. Even with huge popularity this strategy is able to deliver amazing returns, tis is possible because a) There is still huge potential in the market for options selling and b) Use of efficient processing, the faster we process the better results we get.

Please get in touch with us for a detailed analysis of the strategy.

Disclaimer

- The results presented are based on backtest we conducted on the NIFTY options

- We have assumed market to be highly liquid, which might not be absolutely true in real scenario

- We have not incorporated brokerage charges as it differs from one broker to another. Besides the brokerage charged by discount brokers are nominal compared to the gains mentioned.